flowchart LR

A[Raw FASTQ] --> B[QC + Adapter<br/>fastp/MultiQC]

B --> C[Alignment<br/>bwa-mem2]

C --> D[Add Read Groups]

D --> E[Mark Duplicates<br/>GATK]

E --> F[BQSR]

F --> G[Contamination<br/>Check]

G --> H[Mutect2]

H --> I[Filter<br/>Calls]

I --> J[Annotation<br/>VEP]

%% Define the yellow style class

classDef covered fill:#ffeb3b,stroke:#333,stroke-width:2px;

%% Apply the class to specific nodes

class B,H,I,J covered;

Cancer Variant Analysis

Introduction to Cancer Genomics and Variant Detection

2025-12-12

Learning Objectives

After this session, you will be able to:

- Understand why cancer is fundamentally a genomic disease

- Distinguish between somatic and germline variants

- Identify different types of mutations in cancer

- Understand sequencing approaches for cancer genomics

- Comprehend the bioinformatics workflow for variant detection

- Appreciate the clinical relevance of variant calling

Cancer: A Disease of the Genome

Key characteristics:

- Abnormal cell growth - uncontrolled proliferation

- Invasive potential - ability to spread (metastasis)

- Initiated by acquired genomic mutations affecting cell growth regulators

- Mutations occur stochastically, but rate influenced by environment

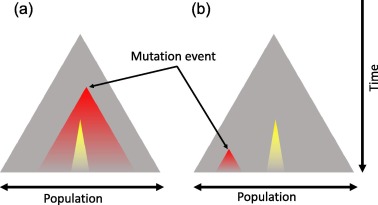

- Clonal evolution - natural selection of malignant cells

Driver vs Passenger Mutations

Cancer genomes typically harbor 2-8 driver mutations (Vogelstein et al., 2013), though this varies by cancer type. Pediatric cancers often have fewer drivers, while hypermutated adult cancers may have more. Drivers represent a small minority of total mutations.

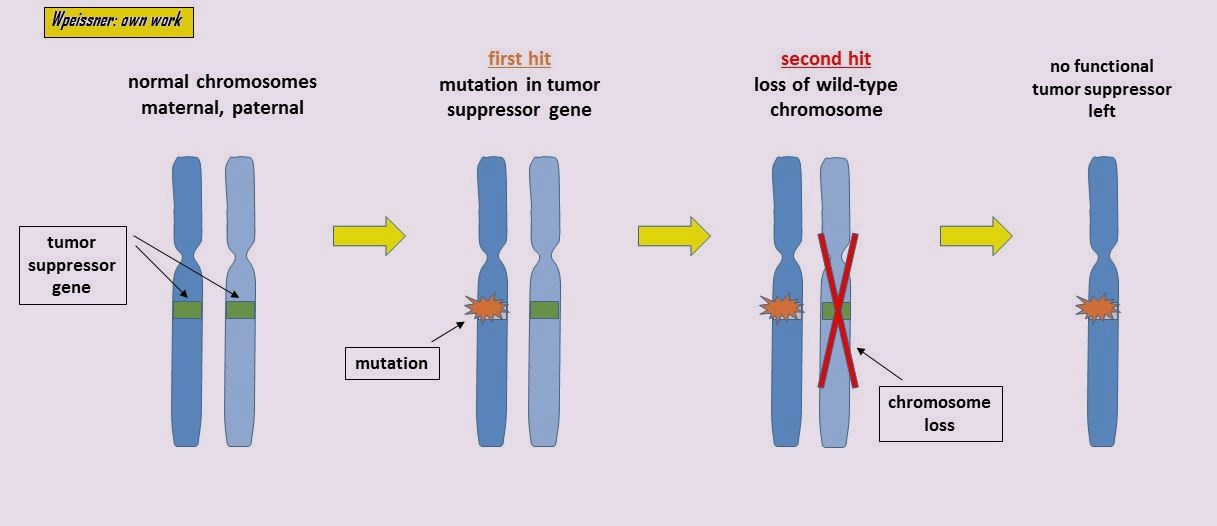

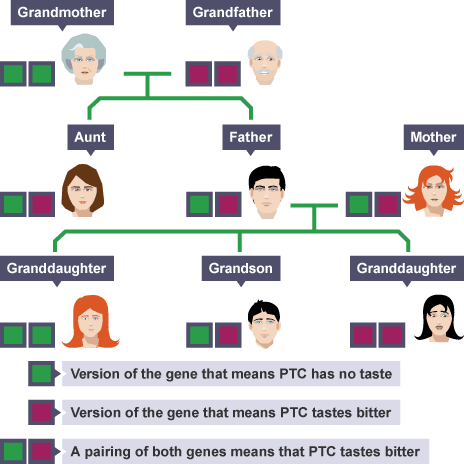

Hereditary vs Sporadic Cancer

Sporadic (~90-95%)

- Acquired somatic mutations

- Accumulate during lifetime

- Environmental factors contribute

Hereditary (~5-10%)

- Inherited predisposition alleles

- BRCA1/2 (breast, ovarian)

- Lynch syndrome genes (colorectal)

- Still require somatic “second hits”

Clinical Relevance

Hereditary cancer syndromes have implications for family screening, risk reduction, and treatment options (e.g., PARP inhibitors for BRCA carriers).

The Hallmarks of Cancer

8 Core Hallmarks:

| Hallmark | Description |

|---|---|

| Sustaining proliferative signaling | Self-sufficiency in growth signals |

| Evading growth suppressors | Insensitivity to anti-growth signals |

| Resisting cell death | Evading apoptosis |

| Enabling replicative immortality | Limitless replicative potential |

| Inducing angiogenesis | Sustained blood vessel formation |

| Activating invasion & metastasis | Tissue invasion and spread |

| Avoiding immune destruction | Escaping immune surveillance |

| Deregulating cellular energetics | Altered metabolism (Warburg effect) |

2 Enabling Characteristics: Genome instability & mutation; Tumor-promoting inflammation

Reference

Hanahan & Weinberg (2011) “Hallmarks of Cancer: The Next Generation” - Cell

Variant Terminology: Essential Definitions

Mutation: The process of change in DNA

Variant: A difference in DNA sequence compared to a reference (the outcome)

Somatic variant: Occurs only in specific cells/tissues - Not inherited - Arises during lifetime

Germline variant: Present in all cells - Can be passed to offspring - Present from conception

Polymorphism: Traditionally defined as variant >1% frequency in population (though “variant” is now preferred terminology)

Mutation vs Variant: A Practical Example

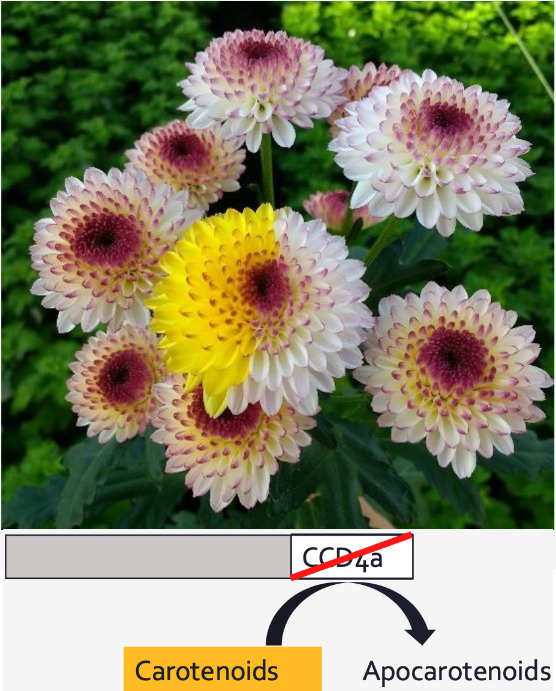

The Yellow Flower Example:

- Mutation: The change in DNA that caused petals to turn yellow

- Variant: The resulting DNA difference between yellow and white flowers

This is a somatic mutation - occurring during the plant’s development in one branch, analogous to somatic mutations in cancer.

The CCD4a gene mutation prevents breakdown of carotenoids, leading to yellow pigmentation.

Types of Mutations in Cancer

Small-scale mutations

- SNVs (Single Nucleotide Variants)

- INDELs (Insertions and Deletions)

Structural variations

- Large INDELs (>50bp)

- Translocations - chromosomal rearrangements

- Inversions - reversed DNA segments

- Fusion transcripts - gene fusions from translocations

- CNV (Copy Number Variation) - gains/losses of genomic regions

LOH (Loss of Heterozygosity) is a consequence of CNV or copy-neutral events, not a mutation type itself.

Clinical Relevance

Different mutation types require different detection methods and have distinct clinical implications for treatment selection.

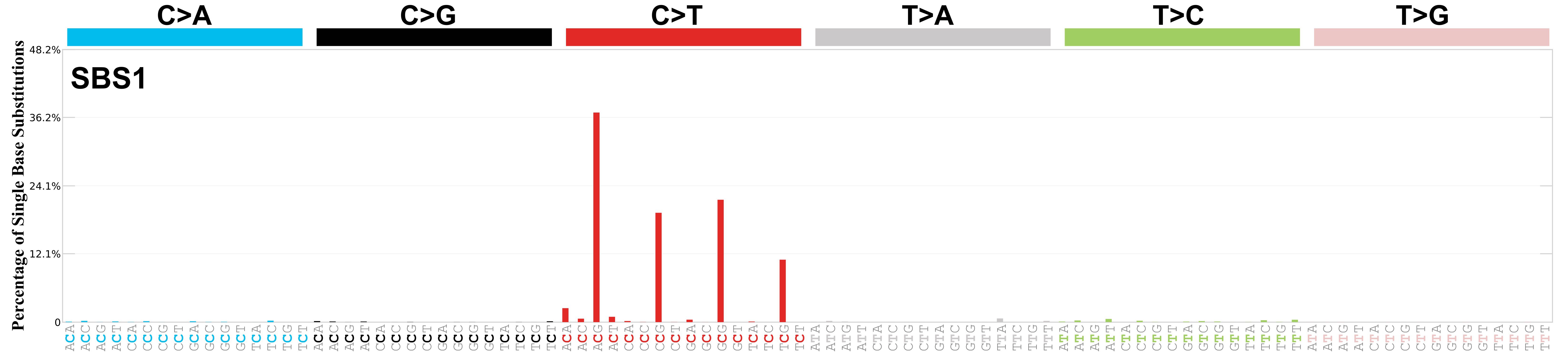

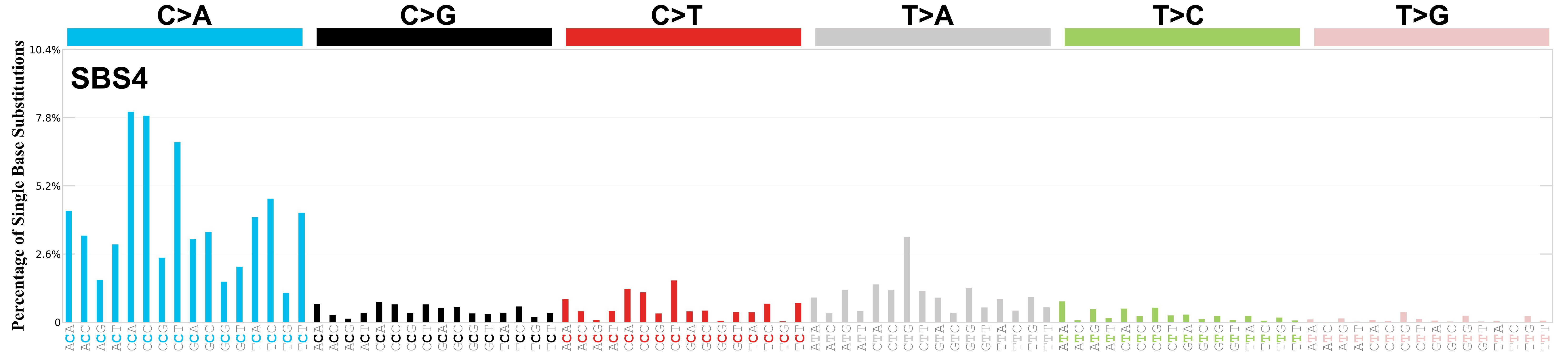

Mutational Signatures: Fingerprints of Mutagenesis

Each mutational process leaves a characteristic pattern:

Signature 1: Aging, C>T at CpG sites, Transition (Py \(\leftrightarrow\) Py)

Signature 4: Tobacco smoking, C>A, Transversion (Py \(\leftrightarrow\) Pu)

Signature 6: Mismatch repair (MMR) deficiency

Signature 7: UV light, C>T at dipyrimidines, Transition

Clinical applications:

- Understanding tumor etiology (e.g. Signature 4, 7)

- Treatment selection (e.g., PARP inhibitors for HRD) (Signature 3)

- Immunotherapy response prediction (Signature 6)

Transition: Swapping similar shapes (Purine \(\leftrightarrow\) Purine or Pyrimidine \(\leftrightarrow\) Pyrimidine). Transversion: Swapping different shapes (Purine \(\leftrightarrow\) Pyrimidine).

Reference

Alexandrov et al. (2020) “The repertoire of mutational signatures in human cancer” - Nature

Sequencing Strategies for Cancer Genomics

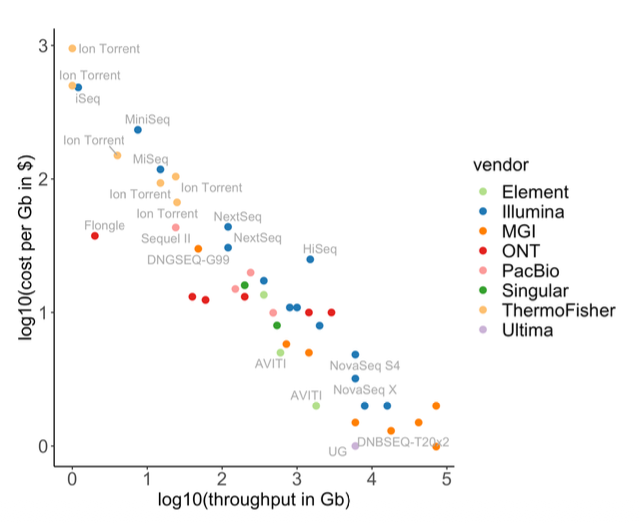

Coverage strategies

- Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS)

- Complete genome coverage

- Detects all variant types

- Best for structural variants

- Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) (Bait Capture)

- Protein-coding regions only

- Cost-effective (

WES 100x: 25 M 2 x 100 bp

WGS 30x: 450 M 2 x 100 bp

) - Misses non-coding regions

- Custom panels (Bait Capture, mostly)

- Targeted cancer genes

- Deep coverage

Sequencing technologies

Short reads (2x150bp standard):

- Illumina, MGI, Element, Ultima

- High accuracy, mature pipelines

Long reads:

- PacBio HiFi: >Q30 accuracy

- Oxford Nanopore: Q20+ with R10.4.1

- Superior for SVs and phasing

Depth Recommendations

WGS: 60-100x tumor, 30-40x normal WES: 100-200x ctDNA: 10,000-30,000x

Experimental Design: Tumor-Normal Pairs

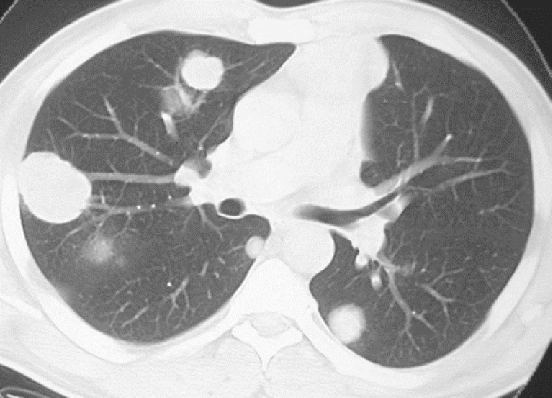

The challenge: Tumor tissue is heterogeneous - contains: - Tumor cells - Immune infiltrates - Stromal cells - Normal tissue

Solution: Paired samples

- Tumor sample - from the malignancy

- Normal sample - typically blood

For hematological malignancies, use skin biopsy or buccal swab (blood IS the tumor!)

Tumor Purity

Typical tumor purity ranges from 30-80%. Samples below 20-30% purity may have insufficient power for reliable somatic variant detection. Consider pathologist review or microdissection.

Bioinformatics Workflow Overview

Critical Note

Variant annotation is essential but often overlooked! Without functional annotation and clinical database lookup, variants have limited utility.

Note

Course Scope

The steps highlighted in yellow are directly discussed in this course.

The remaining steps are not mentioned here but are covered in other courses (e.g., NGS - Variant Analysis and NGS - Quality Control, Alignment, Visualisation). However, we provide the scripts for the analysis in the course GitHub repo.

The SAM/BAM/CRAM File Formats

Purpose: Store sequence alignments

Key points:

- SAM: Text-based (Human readable)

- BAM: Lossless binary compressed SAM

- Indexable (Fast random access)

- CRAM: Ref-based compression

- Lossless or Lossy modes

- ~30-60% smaller than BAM

- Requires access to the reference genome for decoding

1. Header (@ lines)

@HD VN:1.6 SO:coordinate

@SQ SN:chr6 LN:170805979

@SQ SN:chr17 LN:83257441

@RG ID:HWI-ST466.C1TD1ACXX.normal LB:normal PL:ILLUMINA SM:normal PU:HWI-ST466.C1TD1ACXX

@PG ID:bwa PN:bwa VN:0.7.17-r1188 CL:bwa mem /config/data/reference//ref_genome.fa /config/data/reads/normal_R1.fastq.gz /config/data/reads/normal_R2.fastq.gz

@PG ID:samtools PN:samtools PP:bwa VN:1.21 CL:samtools sort

@PG ID:samtools.1 PN:samtools PP:samtools VN:1.21 CL:samtools view -bh2. Alignment Record (The actual reads)

| Field | Meaning |

|---|---|

| QNAME | Query / Read Name (read1) |

| FLAG | Bitwise flags describing state (99) |

| RNAME | Reference sequence / Chromosome (chr6) |

| POS | 1-based mapping position (1000) |

| MAPQ | Mapping quality / Confidence (60) |

| CIGAR | Alignment String (76M) |

| SEQ | Nucleotide sequence (ATGC...) |

| QUAL | Base quality scores (####) |

Additional SAM fields in this example

- RNEXT =

=(mate maps to same chromosome) - PNEXT =

1150(mate’s mapping position)

- TLEN =

226(template/insert length in bp)

Resource

Learn more at the SIB course:

Marking PCR Duplicates

Why it matters:

- Variant callers assume each read is an independent observation

- PCR/optical duplicates violate this assumption

- Can lead to false positive variant calls

Solution:

- Mark duplicates based on alignment coordinates

- Use Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) for accurate deduplication - especially important for low-input and ctDNA samples

Tool: gatk MarkDuplicates

Read Groups: Organizing Your Data

Purpose: Track metadata for groups of reads within BAM files

Key Read Group Tags:

- ID: Unique read group identifier

- SM: Sample name (patient/specimen)

- Critical for multi-sample calling

- Tumor vs. Normal distinction

- LB: Library prep identifier

- Used for duplicate marking

- PL: Sequencing platform

- PU: Platform unit (flowcell.lane)

- For tracking batch effects

Why read groups matter:

- BQSR: Models built per-read-group

- Merging: Combine multiple lanes/runs per sample

- Duplicate marking: Per-library detection

- Somatic calling: Required to distinguish tumor/normal

- QC & troubleshooting: Track technical artifacts

Header Example (Tumor-Normal Pair):

Normal:

Tumor:

Alignment Record with Read Group:

| Tag | Value | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| RG:Z: | tumor.lane1 |

Links read to @RG ID:tumor.lane1 |

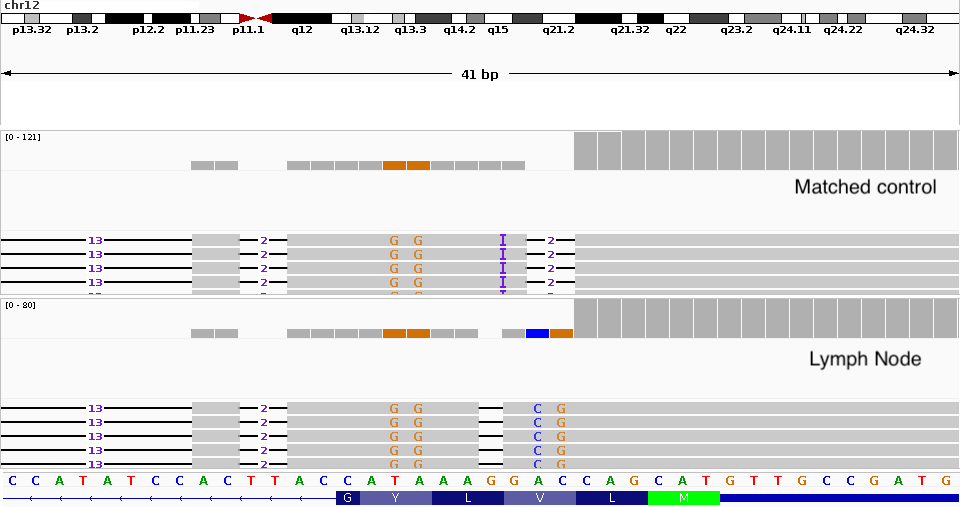

Somatic Variant Calling Context

Mutect2 uses the SM: field to identify tumor and normal samples. Without proper read groups, somatic callers cannot distinguish between samples!

Somatic Variant Calling Challenges

Germline calling assumes:

- Heterozygous: ~50% VAF (typically 30-70% due to technical variation)

- Homozygous: ~100% VAF

These assumptions fail in tumors:

- Variable tumor purity (30-80%, which is effectively contamination by normal cells)

- Clonal heterogeneity (subclones)

- Copy number alterations

- VAF can be anywhere from <1% to 100%

Additional challenges:

- Sequencing errors, alignment artifacts

- FFPE artifacts

- C>T/G>A deamination

- 8-oxoG which causes the G>T transversions

- Sample contamination

Let’s make an example (assuming diploid genome and CN=2)

1. The Ideal Case

Sample is 100% Tumor

If a mutation is heterozygous (1 of 2 alleles): \[\text{VAF} = \frac{1}{2} = \mathbf{50\%}\]

To a caller, this looks like a clear, standard germline variant.

2. Closer to reality

Sample is 40% Tumor (60% Normal)

The normal cells (wild type) dilute the signal. \[\text{VAF} = \frac{\text{Purity}}{2}\] \[\text{VAF} = \frac{0.40}{2} = \mathbf{20\%}\]

Real-world complications

Aneuploidy complicates this further: In real cases, copy number alterations can dramatically change expected VAF. For example, if the mutation is on a region with CN=4, the math becomes more complex.

Tumor-infiltrated controls: Matched control samples can also be tumor-infiltrated, making it sometimes impossible to distinguish true somatic variants from germline or contamination.

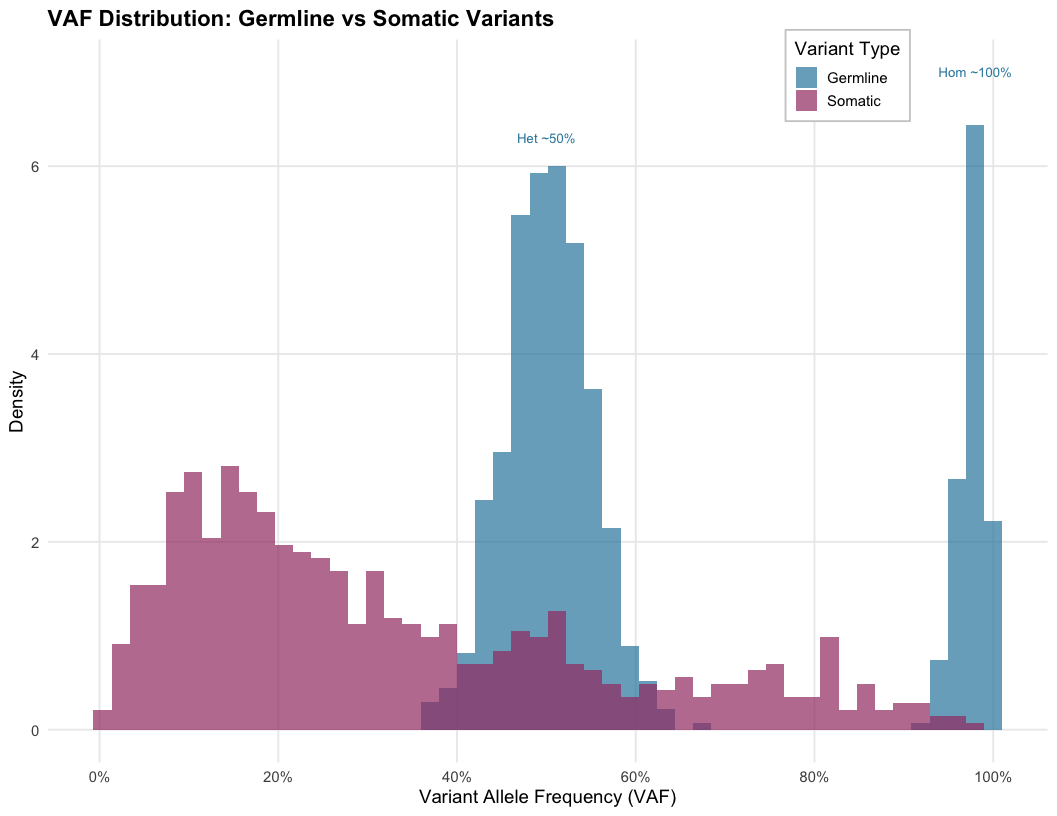

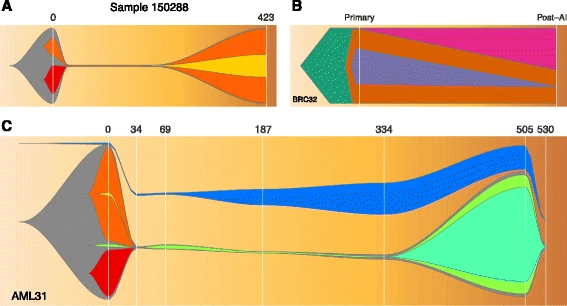

Tumor Purity, Ploidy, and Clonality

Key concepts:

Tumor purity: Fraction of tumor cells in sample

Ploidy: Average copy number across genome (often >2 in cancer)

Clonal variants: Present in all tumor cells

Subclonal variants: Present in a subset of tumor cells

VAF interpretation examples:

- Pure tumor (100%), clonal het variant → VAF ≈ 50%

- 50% purity, clonal het variant → VAF ≈ 25%

- 50% purity, subclonal variant (20% of cells) → VAF ≈ 5%

Clinical Relevance

Subclonal variants can become dominant after treatment selection pressure, leading to resistance.

Variant Filtering Strategies

Three key considerations:

1. Sequencing Error

- Base quality scores (Phred: Q30 = 1/1000 error)

- Variant allele frequency

- Strand bias

- Mapping quality (ie MAPQ ≥ 20)

2. Technical Artifacts

- Panel of Normals (PoN): Database of artifacts seen in normal samples

- Systematic errors from library prep or sequencing

- FFPE artifacts

3. Germline Filtering

- Compare with matched normal

- Filter using population databases:

- gnomAD v4.0 (>800K individuals)

- 1000 Genomes Phase 3 (~2,500 individuals)

- Common variants (AF > 0.1%) are typically germline

gnomAD

The Genome Aggregation Database contains variant frequencies essential for filtering common germline variants. Most callers (Mutect2, Strelka2) apply these filters automatically, but understanding the logic helps with troubleshooting false positives.

GATK Mutect2 Workflow

flowchart TD

A[Tumor BAM] --> C[Mutect2]

B[Normal BAM] --> C

D[Panel of Normals] --> C

E[Germline Resource] --> C

A -.-> |optional| F[GetPileupSummaries]

E -.-> F

F -.-> G[CalculateContamination]

G -.-> |if available| H

C --> H[FilterMutectCalls]

H --> I[Filtered VCF]

I --> J[VEP Annotation]

Key features:

- Haplotype-aware variant calling (local assembly)

- Joint analysis of tumor-normal pairs

- Integrated contamination estimation

- F1R2 (Forward 1st, Reverse 2nd) artifact filtering

PoN vs gnomAD

- Germline Resource: Filters biological germline variants (universal)

- PoN: Filters technical artifacts (platform-specific)

Public PoNs exist but work best when your sequencing protocol matches theirs. When in doubt, build your own!

You can find every step’s relative script here

The VCF File Format

Variant Call Format Standard for storing variant data (current: v4.3)

##fileformat=VCFv4.3

##INFO=<ID=DP,Number=1,Type=Integer,Description="Total Depth">

##INFO=<ID=AF,Number=A,Type=Float,Description="Allele Frequency">

##FILTER=<ID=weak_evidence,Description="Insufficient support">

##FILTER=<ID=germline,Description="Likely germline variant">

##FORMAT=<ID=GT,Number=1,Type=String,Description="Genotype">

##FORMAT=<ID=AD,Number=R,Type=Integer,Description="Allelic depths (REF,ALT)">

##FORMAT=<ID=AF,Number=A,Type=Float,Description="Allele Frequency">

#CHROM POS ID REF ALT QUAL FILTER INFO FORMAT TUMOR NORMAL

chr17 7577538 rs123 G A . PASS DP=100 GT:AD:AF 0/1:70,30:0.30 0/0:50,0:0.0

chr17 7578406 . C T . germline DP=85 GT:AD:AF 0/1:40,45:0.53 0/1:30,25:0.45Key columns explained:

- CHROM/POS: Genomic location

- REF/ALT: Reference and alternate alleles

- FILTER: Quality filters applied (PASS = passed all)

- FORMAT: Defines sample-specific fields

- GT: Genotype (0/0=hom ref, 0/1=het, 1/1=hom alt)

- AD: Allele depths (REF count, ALT count)

- AF: Variant Allele Frequency = ALT/(REF+ALT)

Example interpretation:

Row 1: Somatic mutation (30% VAF in tumor, 0% in normal) ✓

Row 2: Germline variant (present in both tumor and normal) ✗

FILTER Field

“PASS” means the variant passed all filters, not that it’s biologically validated. Clinical decisions require orthogonal validation (Sanger, ddPCR, amplicon-seq).

Variant Annotation: The Critical Step

After calling, variants need biological context:

Functional Annotation

- VEP (Ensembl) or SnpEff

- Effect prediction: missense, nonsense, splice site

- Impact assessment: SIFT, PolyPhen, CADD scores

Clinical Databases

- ClinVar: Clinical significance

- COSMIC: Cancer mutation database

- OncoKB, CIViC: Actionability

Population Frequencies

- gnomAD, dbSNP

- Filter common germline variants

Tools

VEP offers extensive plugin ecosystem.

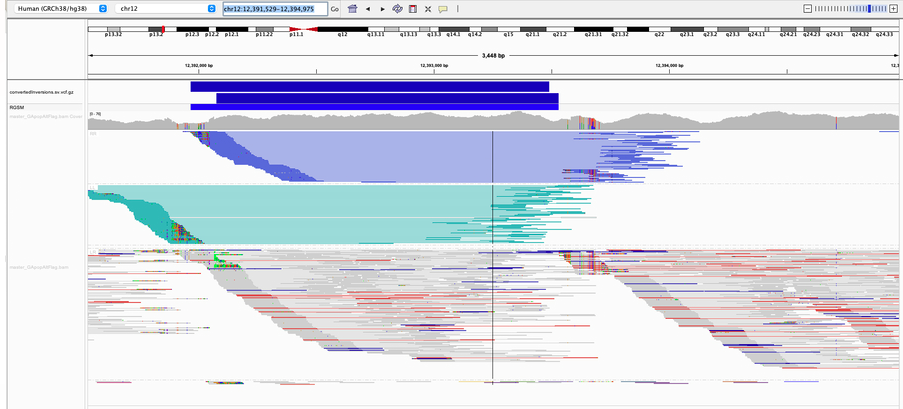

Structural Variation Detection

Types:

- Large insertions/deletions

- Translocations

- Inversions

- Complex rearrangements

Detection methods:

- Discordant read pairs

- Split reads

- Read depth changes

- Assembly-based approaches

Tools: Manta, Tiddit, GRIDSS2, DELLY, Sniffles2 (long reads)

Long Reads Advantage

Long-read sequencing (PacBio HiFi, ONT) dramatically improves structural variant detection, especially for complex rearrangements and insertions.

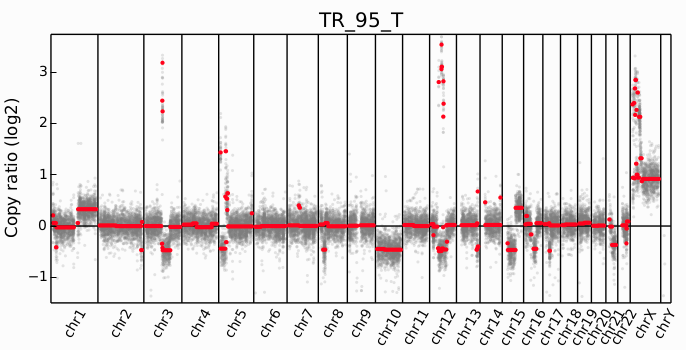

Copy Number Variation (CNV)

Characteristics:

- Gains or losses of genomic segments

- Full chromosome or arm-level events common

- Can cause Loss of Heterozygosity (LOH)

Detection approach:

- Calculate coverage in bins

- Normalize for GC content and mappability

- Compare tumor vs normal ratio

- Segment and call CNV regions

Tools: CNVkit, ASCAT, Control-FREEC, PURPLE

Clinical Example

ERBB2 (HER2) amplification in breast cancer determines eligibility for trastuzumab. MYC amplification is prognostic in many cancers.

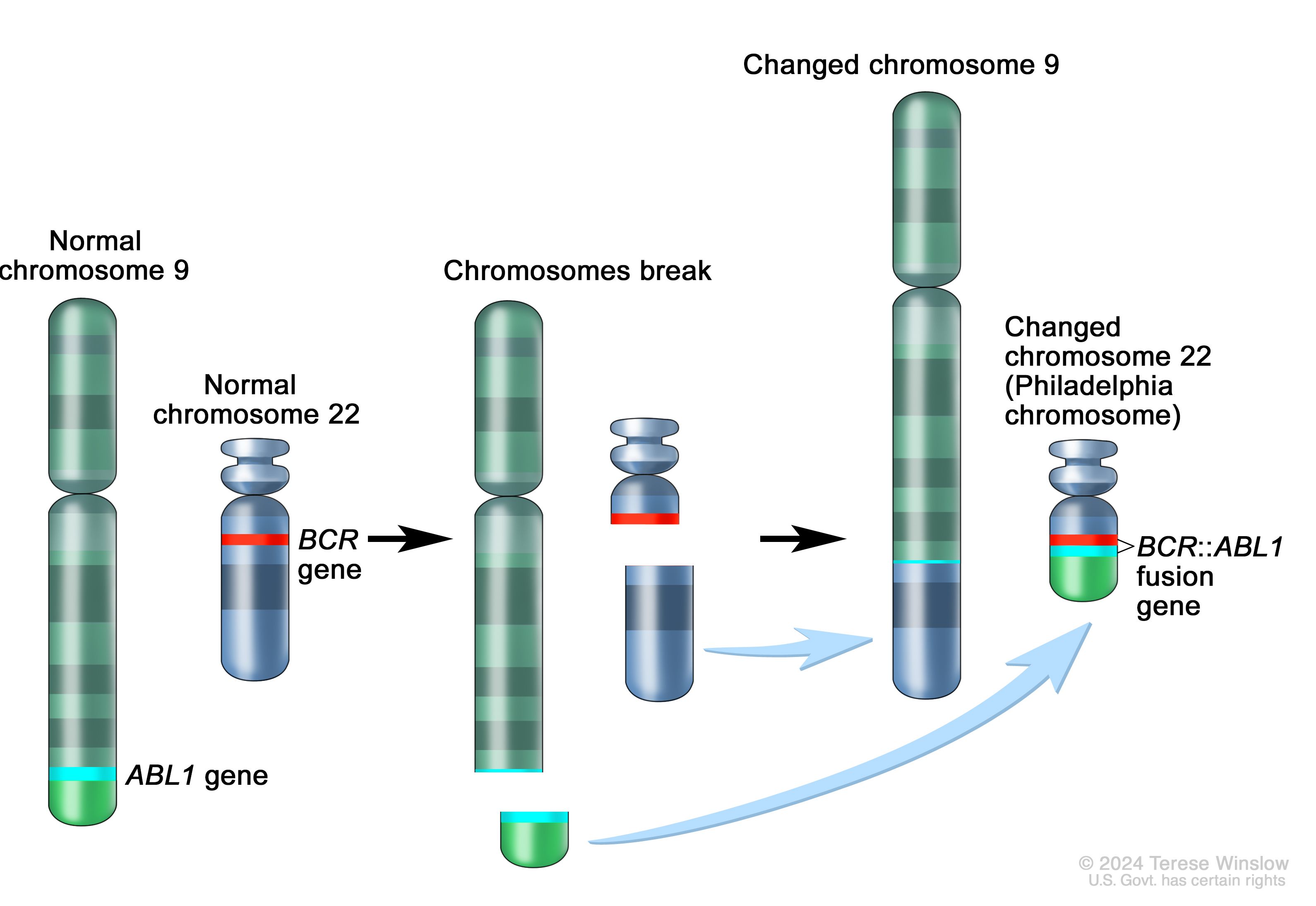

Gene Fusions in Cancer

Mechanism:

- Chromosomal translocation

- Fusion of gene elements

- Creates chimeric transcripts

Detection data types:

- WGS (genomic breakpoints)

- WES (if breakpoints in exons)

- RNA-seq (fusion transcripts)

Detection method: Discordant alignments where paired reads map to different genes/chromosomes

Tools: Manta (DNA), STAR-Fusion, Arriba (RNA-seq)

Famous Example

BCR-ABL fusion in CML(Chronic Myeloid Leukemia)

- discovered 1960

- translocation identified 1973

- imatinib approved 2001.

From observation to targeted therapy took 41 years; today we can do this computationally.

Quality Control Metrics

Essential QC checks at each stage:

| Metric | Expected Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Mapping rate | >95% | Low = contamination or poor quality |

| Duplicate rate | <30% (WGS) | High = low library complexity |

| Mean coverage | As specified | Low = insufficient data |

| Coverage uniformity | CV <0.2 | High variability = capture issues |

| Contamination | <1-2% | High = sample swap or cross-contamination |

| Ti/Tv ratio | ~2.0-2.1 (WGS), ~3.0-3.3 (exome) | Low = sequencing errors enriched |

| Insert size | 200-400bp (Illumina) | Bimodal = library issues |

| GC bias | Flat across 30-70% GC | Strong bias = PCR or coverage issues |

Tools: fastQC, MultiQC, mosdepth, GATK CollectHsMetrics

Summary and Key Takeaways

Cancer Genomics Fundamentals:

- Cancer is driven by genomic alterations

- Both small variants and structural changes

- Somatic vs germline distinction critical

- ~5-10% hereditary predisposition

Technical Considerations:

- Tumor-normal paired design

- Appropriate sequencing strategy

- Quality preprocessing essential

- Purity >30% recommended

Variant Calling:

- Haplotype-aware methods (Mutect2)

- Multiple filtering strategies

- Standard file formats (BAM, VCF)

- Annotation is essential!

Clinical Applications:

- Mutational signatures reveal etiology

- TMB predicts immunotherapy response

- Fusions guide targeted therapy

- CNV determines treatment options

References and Resources

Key Papers:

- Hanahan & Weinberg (2011) Cell - Hallmarks of Cancer

- Vogelstein et al. (2013) Science - Cancer Genome Landscapes

- Alexandrov et al. (2020) Nature - Mutational Signatures

- Cibulskis et al. (2013) Nature Biotech - MuTect

- Karczewski et al. (2020) Nature - gnomAD

Databases:

- COSMIC (cancer.sanger.ac.uk) - Somatic mutations

- gnomAD (gnomad.broadinstitute.org) - Population frequencies

- ClinVar - Clinical interpretations

- OncoKB - Precision oncology knowledge

Tools & Pipelines:

- GATK (gatk.broadinstitute.org)

- nf-core/sarek - Production pipeline

- IGV (igv.org) - Visualization

Exercises

Giphy

Cancer Variant Analysis - SIB