Decorating and optimising a Snakemake workflow

Learning outcomes

After having completed this chapter you will be able to:

- Use non-file parameters and config files in rules

- Make a workflow process list of inputs rather than one at a time

- Modularise a workflow

- Aggregate final outputs in a target rule

- (Optimise resource usage in a workflow)

- (Create rules with non-conventional outputs)

Material

Snakefile from previous session

If you didn’t finish the previous part or didn’t do the optional exercises, you can restart from a fully commented Snakefile, with log messages and benchmarks implemented in all rules. You can download it here or download it in your current directory with:

wget https://raw.githubusercontent.com/sib-swiss/containers-snakemake-training/main/docs/solutions_day2/session2/workflow/Snakefile

Exercises

This series of exercises focuses on how to improve the workflow that you developed in the previous session. As a result, you will add only one rule to your workflow. But, fear not, it’s a crucial one!

Development and back-up

During this session, you will modify your Snakefile quite heavily, so it may be a good idea to make back-ups from time to time (with cp or a simple copy/paste) or use a versioning system. As a general rule, if you have a doubt on the code you are developing, do not hesitate to make a back-up beforehand.

Using non-file parameters and config files

Non-file parameters

As you have seen, Snakemake execution revolves around input and output files. However, a lot of software also use non-file parameters to run. In the previous presentation and series of exercises, we advocated against using hard-coded file paths. Yet, if you look back at previous rules, you will find two occurrences of this behaviour in shell directives:

- In rule

read_mapping, the index parameter:-x resources/genome_indices/Scerevisiae_index - In rule

reads_quantification_genes, the annotation parameter:-a resources/Scerevisiae.gtf

This reduces readability and makes it very hard to change the values of these parameters, because this requires to change the shell directive code.

The params directive was (partly) designed to solve this problem: it contains parameters and variables that can be accessed in the shell directive. It allows to specify additional non-file parameters instead of hard-coding them into shell commands or using them as inputs/outputs.

Main properties of parameters from the params directive

- Their values can be of any type (integer, string, list…)

- Their values can depend on wildcard values and use input functions (explained here). This means that parameters can be changed conditionally, for example depending on the value of a wildcard

- In contrast to the

inputdirective, theparamsdirective can take more arguments than onlywildcards, namelyinput,output,threads, andresources

- In contrast to the

- Similarly to

{input}and{output}placeholders, they can be accessed from within theshelldirective with the{params}placeholder - Multiple parameters can be defined in a rule (do not forget the comma between each entry!) and they can also be named. While it isn’t mandatory, un-named parameters are not explicit at all, so you should always name your parameters

Here is an example of params utilisation:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | |

Exercise: Pick one of the two hard-coded paths mentioned earlier and replace it using params.

Answer

You need to add a params directive to the rule, name the parameter and replace the path by the placeholder in the shell directive. We did this for both rules so that you can check everything. Feel free to copy this in your Snakefile. For clarity, only lines that changed are shown below:

-

read_mapping:1 2 3 4 5 6

params: index = 'resources/genome_indices/Scerevisiae_index' shell: 'hisat2 --dta --fr --no-mixed --no-discordant --time --new-summary --no-unal \ -x {params.index} --threads {threads} \ # Parameter was replaced here -1 {input.trim1} -2 {input.trim2} -S {output.sam} --summary-file {output.report} 2>> {log}' -

reads_quantification_genes:1 2 3 4 5 6

params: annotations = 'resources/Scerevisiae.gtf' shell: 'featureCounts -t exon -g gene_id -s 2 -p --countReadPairs \ -B -C --largestOverlap --verbose -F GTF \ -a {params.annotations} -T {threads} -o {output.gene_level} {input.bam_once_sorted} &>> {log}' # Parameter was replaced here

But doing this only shifted the problem: now, hard-coded paths are in params instead of shell. This is better, but not by much! Luckily, there is an even better way to handle parameters: instead of hard-coding parameter values in the Snakefile, Snakemake can use parameters (and values) defined in config files.

Config files

Config files are stored in the config subfolder and written in JSON or YAML format. You will use the latter for this course as it is more user-friendly. In .yaml files:

- Parameters are defined with the syntax

<name>: <value> - Values can be strings, integers, booleans…

- For a complete overview of available value types, see this list

- A parameter can have multiple values, each value being on an indented line starting with “-“

- These values will be stored in a Python list when Snakemake parses the config file

- Parameters can be named and nested to have a hierarchical structure, each sub-parameter and its value being on an indented lines

- These parameters will be stored as a dictionary when Snakemake parses the config file

Config files will be parsed by Snakemake when executing the workflow, and parameters and their values will be stored in a Python dictionary named config. The config file path can be specified in the Snakefile with configfile: <path/to/file.yaml> at the top of the file, or at runtime with the execution parameter --configfile <path/to/file.yaml>.

The example below shows a parameter with a single value (lines_number), a parameter with multiple values (samples), and nested parameters (resources):

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

Then, each parameter can be accessed in Snakemake with:

1 2 3 4 | |

Accessing config values in shell

You cannot use values from the config dictionary directly in a shell directive. If you need to access parameter value in shell, first define it in params and assign its value from the dictionary, then use params.<name> in shell.

Exercise: Create a config file in YAML format and fill it with variables and values to replace one of the two hard-coded parameters mentioned before. Then replace the hard-coded parameter values by variables from the config file. Finally, add the config file import on top of your Snakefile.

Answer

First, create an empty config file:

touch config/config.yaml # Create empty config file

Then, fill it with the desired values:

1 2 3 4 5 | |

Then, replace the params values in the Snakefile. We did this for both rules so that you can check everything. Feel free to copy this in your Snakefile. For simplicity, only lines that changed are shown below:

-

read_mapping:1 2

params: index = config['index'] -

reads_quantification_genes:1 2

params: annotations = config['annotations']

Finally, add the file path on top of the Snakefile:

configfile: 'config/config.yaml'

From now on, if you need to change these values, you can easily do it in the config file instead of modifying the code!

Modularising a workflow

If you develop a large workflow, you are bound to encounter some cluttering problems. Have a look at your current Snakefile: with only four rules, it is already almost 150 lines long. Imagine what happens when your workflow has dozens of rules? The Snakefile may (will?) become messy and harder to maintain and edit. This is why it quickly becomes crucial to modularise your workflow. This approach also makes it easier to re-use pieces of one workflow into another. Snakemake can be modularised on three different levels:

-

The most fine-grained level is wrappers

More information on wrappers

Wrappers allow to quickly use popular tools and libraries in Snakemake workflows, thanks to the

wrapperdirective. Wrappers are automatically downloaded and deploy a conda environment when running the workflow, which increases reproducibility. However their implementation can be ‘rigid’ and sometimes it may be better to write your own rule. See the official documentation for more explanations -

For larger parts belonging to the same workflow, it is recommended to split the main Snakefile into smaller snakefiles, each containing rules with a common topic. Smaller snakefiles are then integrated into the main Snakefile with the

includestatement. In this case, all rules share a common config file. See the official documentation for more explanationsRules organisation

There is no official guideline on how to regroup rules, but a simple and logic approach is to create “thematic” snakefiles, i.e. place rules related to the same topic in the same file. Modularisation is a common practice in programming in general: it is often easier to group all variables, functions, classes… related to a common theme into a single script, package, software…

-

The final level of modularisation is modules

More on modules

It enables combination and re-use of rules in the same workflow and between workflows. This is done with the

modulestatement, similarly to Pythonimport. See the official documentation for more explanations

In this course, you will only use the second level of modularisation. Briefly, the idea is to write a main Snakefile in workflow/Snakefile, to place the other snakefile containing rules in the subfolder workflow/rules (these ‘sub-Snakefile’ should end with .smk, the recommended file extension of Snakemake) and to tell Snakemake to import the modular snakefile in the main Snakefile with the include: <path/to/snakefile.smk> syntax.

Exercise: Move your current Snakefile into the subfolder workflow/rules and rename it to read_mapping.smk. Then create a new Snakefile in workflow/ and import read_mapping.smk in it using the include syntax. You should also move the importation of the config file from the modular Snakefile to the main one.

Answer

First, move and rename the main Snakefile:

1 2 | |

Then, add include and configfile statements to the new Snakefile. It should resemble this:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | |

Finally, remove the config file import (configfile: 'config/config.yaml') from the modular snakefile (workflow/rules/read_mapping.smk).

Relative paths

- Include statements are relative to the directory of the Snakefile in which they occur. For example, if the Snakefile is in

workflow, then Snakemake will search for included snakefiles inworkflow/path/to/other/snakefile, regardless of the working directory - You can place snakefiles in a sub-directory without changing input and output paths, because these paths are relative to the working directory

- However, you will need to edit paths to external scripts and conda environments, because these paths are relative to the snakefile from which they are called (this will be discussed in the last series of exercises)

If you have trouble visualising what an include statement does, you can imagine that the entire content of the included file gets copied into the Snakefile. As a consequence, syntaxes like rules.<rule_name>.output.<output_name> can still be used in modular snakefiles, even if the rule <rule_name> is defined in another snakefile. However, you have to make sure that the snakefile in which <rule_name> is defined is included before the snakefile that uses rules.<rule_name>.output. This is also true for input functions and checkpoints.

Using a target rule instead of a target file

Modularisation also offers a great opportunity to facilitate workflows execution. By default, if no target is given in the command line, Snakemake executes the first rule in the Snakefile. So far, you have always executed the workflow with a target file to avoid this behaviour. But we can actually use this property to make execution easier by writing a pseudo-rule (also called target-rule and usually named rule all) which contains all the desired outputs files as inputs in the Snakefile. This rule will look like this:

1 2 3 4 5 | |

Exercise: Implement a rule all in your Snakefile to generate the final outputs by default when running snakemake without specifying a target. Then, test your workflow with a dry-run and the -F parameter. How many rules does Snakemake run?

Content of a rule all

- A rule is not required to have an output nor a

shelldirective - Inputs of rule

allshould be the final outputs that you want to generate, here those of rulereads_quantification_genes

Answer

reads_quantification_genes is currently creating the last workflow outputs (with the same example as before, results/highCO2_sample1/highCO2_sample1_genes_read_quantification.tsv). We need to use these files as inputs of rule all:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

You can launch a dry-run with:

snakemake -c 4 -F -p -n

You should see all the rules appearing, including rule all, and the job stats:

rule all:

input: results/highCO2_sample1/highCO2_sample1_genes_read_quantification.tsv

jobid: 0

reason: Forced execution

resources: tmpdir=/tmp

Job stats:

job count

-------------------------- -------

all 1

fastq_trim 1

read_mapping 1

reads_quantification_genes 1

sam_to_bam 1

total 5

all.

After several (dry-)runs, you may have noticed that the rule order is not always the same: apart from Snakemake considering the first rule of the workflow as a default target, the order of rules in Snakefile/snakefiles is arbitrary and does not influence the DAG of jobs.

Aggregating outputs to process lists of files

Using a target rule like the one presented in the previous paragraph gives another opportunity to make things easier. In the previous rule all, inputs are still hard-coded… and you know that this is not an optimal solution, especially if there are many samples to process. The expand() function will solve both problems.

expand() is used to generate a list of output files by automatically expanding a wildcard expression to several values. In other words, it will replace a wildcard in an expression by all the values of a list, successively. For instance, expand('{sample}.tsv', sample=['A', 'B', 'C']) will create the list of files ['A.tsv', 'B.tsv', 'C.tsv'].

Exercise: Use an expand syntax to transform rule all to generate a list of final outputs with all the samples. Then, test your workflow with a dry-run and the -F parameter.

Two things are required for an expand syntax

- A Python list of values that will replace a wildcard; here, a sample list

- An output path with a wildcard that can be turned into an

expand()function to create all the required outputs

Answer

First, we need to add a sample list in the Snakefile, before rule all. This list contains all the values that the wildcard will be replaced with:

SAMPLES = ['highCO2_sample1', 'highCO2_sample2', 'highCO2_sample3', 'lowCO2_sample1', 'lowCO2_sample2', 'lowCO2_sample3']

Then, we need to transform the rule all inputs to use the expand function:

expand('results/{sample}/{sample}_genes_read_quantification.tsv', sample=SAMPLES)

The Snakefile should like this:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | |

You can launch a dry-run with the same command as before:

snakemake -c 4 -F -p -n

You should see rule all requiring 6 inputs and all the other rules appearing 6 times (1 for each sample):

rule all:

input: results/highCO2_sample1/highCO2_sample1_genes_read_quantification.tsv, results/highCO2_sample2/highCO2_sample2_genes_read_quantification.tsv, results/highCO2_sample3/highCO2_sample3_genes_read_quantification.tsv, results/lowCO2_sample1/lowCO2_sample1_genes_read_quantification.tsv, results/lowCO2_sample2/lowCO2_sample2_genes_read_quantification.tsv, results/lowCO2_sample3/lowCO2_sample3_genes_read_quantification.tsv

jobid: 0

reason: Forced execution

resources: tmpdir=/tmp

Job stats:

job count

-------------------------- -------

all 1

fastq_trim 6

read_mapping 6

reads_quantification_genes 6

sam_to_bam 6

total 25

But there is an even better solution! At the moment, samples are defined as a list in the Snakefile. Processing other samples still means having to locate and change some chunks of code. To further improve workflow usability, samples can instead be defined in config files, so they can easily be added, removed, or modified by users without actually modifying code.

Exercise: Implement a parameter in the config file to specify sample names and modify the rule all to use this parameter instead of the SAMPLES variable in the expand() syntax.

Answer

First, we need to add the sample names to the config file:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 | |

Then, we need to remove SAMPLES from the Snakefile and use the config file in expand() instead:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

config['samples'] is a Python list containing strings, each string being a sample name. This is because a list of parameters become a list when the config file is parsed. You can launch a dry-run with the same command as before (snakemake -c 4 -F -p -n) and you should see the same jobs.

An even more Snakemake-idiomatic solution

There is an even better and more Snakemake-idiomatic version of the expand() syntax in rule all:

expand(rules.reads_quantification_genes.output.gene_level, sample=config['samples'])

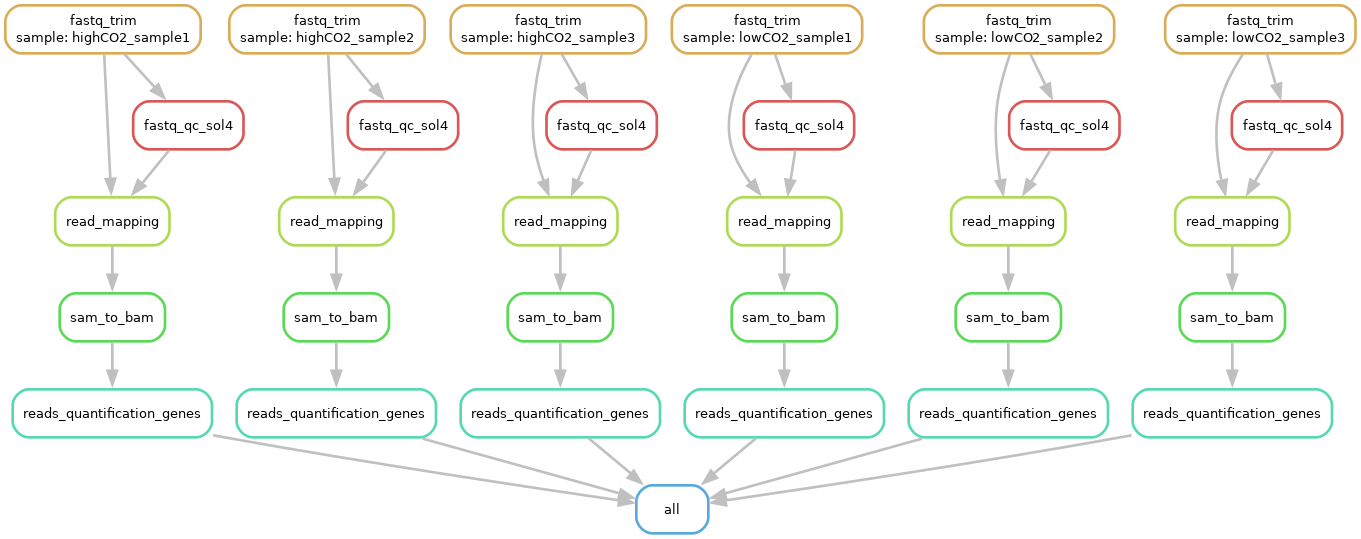

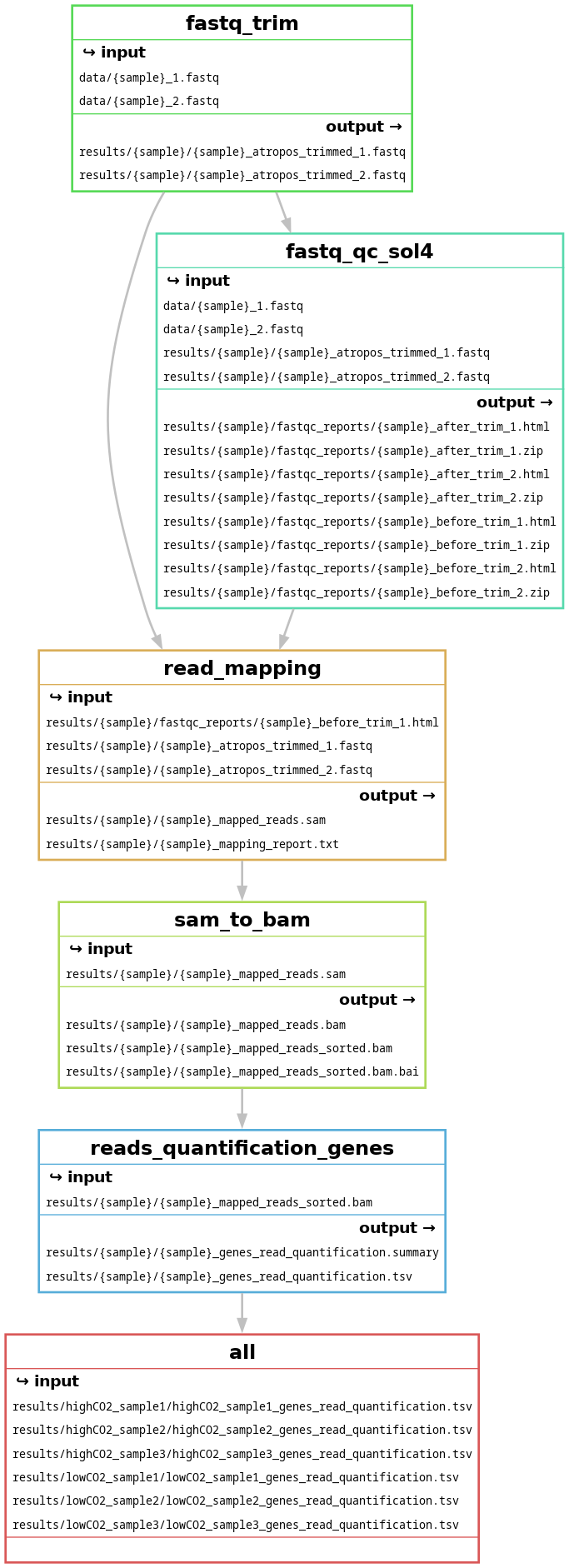

Exercise: Run the workflow on the other samples and generate the workflow DAG and filegraph. If you implemented parallelisation and multithreading in all the rules, the execution should take less than 10 min in total to process all the samples, otherwise it will be a few minutes longer.

Answer

You can run the workflow by removing -F and -n from the dry-run command, which makes a very simple command:

snakemake -c 4 -p --sdm apptainer

To generate the DAG, you can use:

snakemake -c 1 -F -p --dag | dot -Tpng > images/all_samples_dag.png

If needed, open the picture in a new tab to zoom in. Then, you can generate the filegraph with:

snakemake -c 1 -F -p --filegraph | dot -Tpng > images/all_samples_filegraph.png

fastq_qc_sol4. It is the rule implemented in the supplementary exercise below.

Extra: optimising resource usage in a workflow

This part is an extra-exercise about resource usage in Snakemake. It is quite long, so do it only if you finished all the other exercises.

Multithreading

When working with real, larger, datasets, some processes can take a long time to run. Fortunately, computation time can be decreased by running jobs in parallel and using several threads or cores for a single job.

Exercise: What are the two things you need to add to a rule to enable multithreading?

Answer

You need to add:

- The

threadsdirective to tell Snakemake that it needs to allocate several threads to this rule - The software-specific parameters in the

shelldirective to tell a software that it can use several threads

If you add only the first element, the software will not be aware of the number of threads allocated to it and will use its default number of threads (usually one). If you add only the second element, Snakemake will allocate only one thread to the software, which means that it will run slowly or crash (the software expects multiple threads but gets one).

Usually, you need to read documentation to identify which software can make use of multithreading and which parameters control multithreading. We did it for you to save some time:

atropos trim,hisat2,samtools view, andsamtools sortcan parallelise with the--threads <nb_thread>parameterfeatureCountscan parallelise with the-T <nb_thread>parametersamtools indexcan’t parallelise. Remember that multithreading only applies to software that were developed to this end, Snakemake itself cannot parallelise a software!

Unfortunately, there is no easy way to find the optimal number of threads for a job. It depends on tasks, datasets, software, resources you have at your disposal… It often takes of few rounds of trial and error to see what works best. We already decided the number of threads to use for each software:

- 4 threads for

hisat2 - 2 for all the other software

Exercise: Implement multithreading in a rule of your choice (it’s usually best to start by multithreading the longest job, here read_mapping, but the example dataset is small, so it doesn’t really matter).

threads placeholder

threads can also be replaced by a {threads} placeholder in the shell directive.

Answer

We implemented multithreading in all the rules so that you can check everything. Feel free to copy this in your Snakefile:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 | |

Exercise: Do you need to change anything in the snakemake command to run the workflow with 4 cores?

Answer

You need to provide additional cores to Snakemake with the parameter -c 4. Using the same sample as before (highCO2_sample1), the workflow can be run with:

snakemake -c 4 -F -p results/highCO2_sample1/highCO2_sample1_genes_read_quantification.tsv --sdm apptainer

The number of threads allocated to all jobs running at a given time cannot exceed the value specified with --cores, so if you use -c 1, Snakemake will not be able to use multiple threads. Conversely, if you ask for more threads in a rule than what was provided with --cores, Snakemake will cap rule threads at --cores to avoid requesting too many. Another benefit of increasing --cores is to allow Snakemake to run multiple jobs in parallel (for example, here, running two jobs using two threads each).

If you run the workflow from scratch with multithreading in all rules, it should take ~6 min, compared to ~10 min before (i.e. a 40% decrease!). This gives you an idea of how powerful multithreading is when datasets and computing power get bigger!

Things to keep in mind when using parallel execution

- On-screen output from parallel jobs will be mixed, so save any output to log files instead

- Parallel jobs use more RAM. If you run out then either your OS will swap data to disk (which slows data access), or a process will die (which can crash Snakemake)

- Parallelising is not without consequences and has a cost. This is a topic too wide for this course, but just know that using too many cores on a dataset that is too small can slow down computation, as explained here.

Controlling memory usage and runtime

Another way to optimise resource usage in a workflow is to control the amount of memory and runtime of each job. This ensures your instance (computer, cluster…) won’t run out of memory during computation (which could interrupt jobs or even crash the instance) and that your jobs will run in a reasonable amount of time (a job taking more time to run than usual might be a sign that something is going on).

Resource usage and schedulers

Optimising resource usage is especially important when submitting jobs to a scheduler (for instance on a cluster), as it allows a better and more precise definition of your job priority: jobs with low threads/memory/runtime requirements often have a higher priority than heavy jobs, which means they will often start first.

Controlling memory usage and runtime in Snakemake is easier than multithreading: you only need to need to use the resources directive with the memory or runtime keywords and in most software, you don’t even need to specify the amount of memory available to the software via a parameter. Determining how much memory and runtime to use is also easier… after the first run of your workflow. Do you remember the benchmark files you (may have) obtained at the end of the previous series of exercises? Now is the time to take a look at them:

| s | h: m: s | max_rss | max_vms | max_uss | max_pss | io_in | io_out | mean_load | cpu_time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 31.3048 | 0:00:31 | 763.04 | 904.29 | 757.89 | 758.37 | 1.81 | 230.18 | 37.09 | 11.78 |

sandh:m:sgive the job wall clock time (in seconds and hours-minutes-seconds, respectively), which is the actual time taken from the start of a software to its end. You can use these results to infer a safe value for theruntimekeyword- Likewise, you can use

max_rss(shown in megabytes) to figure out how much memory was used by the job and use this value in thememorykeyword

What are the other columns?

In case you are wondering about the other columns of the table, the official documentation has detailed explanations about their content.

Here are some suggested values for the current workflow:

fastq_trim: 500 MBread_mapping: 2 GBsam_to_bam: 250 MBreads_quantification_genes: 500 MB

Exercise: Implement memory usage limit in a rule of your choice.

Two ways to declare memory values

There are two ways to declare memory values in resources:

mem_<unit> = nmem = 'n<unit>': in this case, you must pass a string, so you have to enclosen<unit>with quotes''

<unit> is a unit in [B, KB, MB, GB, TB, PB, KiB, MiB, GiB, TiB, PiB] and n is a float.

Answer

We implemented memory usage control in all the rules so that you can check everything. Rules fastq_trim and read_mapping have the first format while rules sam_to_bam and reads_quantification_genes have the second one. Feel free to copy this in your Snakefile:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 119 120 121 122 | |

Finally, contrary to multithreading, note that you don’t need to change the snakemake command to launch the workflow!

Extra: using non-conventional outputs

This part is an extra-exercise about non-conventional Snakemake outputs. It is quite long, so do it only if you finished all the other exercises.

Snakemake has several built-in utilities to assign properties to outputs that are deemed ‘special’. These properties are listed in the table below:

| Property | Syntax | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Temporary | temp('file.txt') |

File is deleted as soon as it is not required by a future jobs |

| Protected | protected('file.txt') |

File cannot be overwritten after job ends (useful to prevent erasing a file by mistake, for example files requiring heavy computation) |

| Ancient | ancient('file.txt') |

Ignore file timestamp and assume file is older than any outputs: file will not be re-created when re-running workflow, except when --force options are used |

| Directory | directory('directory') |

Output is a directory instead of a file (use touch() instead if possible) |

| Touch | touch('file.txt') |

Create an empty flag file file.txt regardless of shell commands (only if commands finished without errors) |

The next paragraphs will show how to use some of these properties.

Removing and safeguarding outputs

This part shows a few examples using temp() and protected() flags.

Exercise: Can you think of a convenient use of the temp() flag?

Answer

temp() is extremely useful to automatically remove intermediary outputs that are no longer needed.

Exercise: In your workflow, identify outputs that are intermediary and mark them as temporary with temp().

Answer

Unsorted .bam and .sam outputs seem like great candidates to be marked as temporary. One could argue that trimmed .fastq files could also be marked as temporary, but we won’t bother with them here. For clarity, only lines that changed are shown below:

-

rule

read_mapping:1 2

output: sam = temp('results/{sample}/{sample}_mapped_reads.sam'), -

rule

sam_to_bam:1 2

output: bam = temp('results/{sample}/{sample}_mapped_reads.bam'),

Advantages and drawbacks of temp()

On one hand, removing temporary outputs is a great way to save storage space. If you look at the size of your current results/ folder (du -bchd0 results/), you will notice that it drastically increased. Just removing these two files would allow to save ~1 GB. While it may not seem like much, remember that you usually have much bigger files and many more samples!

On the other hand, using temporary outputs might force you to re-run more jobs than necessary if an input changes, so think carefully before using temp().

Exercise: On the contrary, is there a file of your workflow that you would like to protect? If so, mark it with protected().

Answer

Sorted .bam files from rule sam_to_bam seem like good candidates for protection:

1 2 | |

Using an output directory: the FastQC example

FastQC is a program designed to spot potential problems in high-througput sequencing datasets. It is a very popular tool, notably because it is fast and does not require a lot of configuration. It runs a set of analyses on one or more sequence files in FASTQ or BAM format and produces a quality report with plots that summarise the results. It highlights potential problems that might require a closer look in your dataset.

As such, it would be interesting to run FastQC on the original and trimmed .fastq files to check whether trimming actually improved read quality. FastQC can be run interactively or in batch mode, during which it saves results as an HTML file and a ZIP file. You will later see that running FastQC in batch mode is a bit harder than it looks.

Data types and FastQC

FastQC does not differentiate between sequencing techniques and as such can be used to look at libraries coming from a large number of experiments (Genomic Sequencing, ChIP-Seq, RNAseq, BS-Seq etc…).

If you run fastqc -h, you will notice something a bit surprising, but not unusual in bioinformatics:

-o --outdir Create all output files in the specified output directory.

Please note that this directory must exist as the program

will not create it. If this option is not set then the

output file for each sequence file is created in the same

directory as the sequence file which was processed.

-d --dir Selects a directory to be used for temporary files written when

generating report images. Defaults to system temp directory if

not specified.

Two files are produced for each .fastq file and these files appear in the same directory as the input file: FastQC does not allow to specify the output file names! However, you can set an alternative output directory, even though it needs to be manually created before FastQC is run.

There are different solutions to this problem:

- Work with the default file names produced by FastQC and leave the reports in the same directory as the input files

- Create the outputs in a new directory and leave the reports with their default name

- Create the outputs in a new directory and tell Snakemake that the directory itself is the output

- Force a naming convention by manually renaming the FastQC output files within the rule

It would be too long to test all four solutions, so you will work on the 3rd or the 4th solution. Here is a brief summary of solutions 1 and 2:

- This could work, but it’s better not to put reports in the same directory as input sequences. As a general principle, when writing Snakemake rules, we prefer to be in charge of the output names and to have all the files linked to a sample in the same directory

- This involves manually constructing the output directory path to use with the

-oparameter, which works but isn’t very convenient

The first part of the FastQC command is:

fastqc --format fastq --threads {threads} --outdir {folder_path} --dir {folder_path} <input_fastq1> <input_fastq2>

Explanation of FastQC parameters

-t/--threads: specify how many files can be processed simultaneously. Here, it will be 2 because inputs are paired-end files-o/--outdir: create output files in specified output directory-d/--dir: select a directory to be used for temporary files

Choose between solution 3 or 4 and implement it. You will find more information and help below.

This option is equivalent to tell Snakemake not to worry about individual files at all and consider an entire directory as the rule output.

Exercise: Implement a single rule to run FastQC on both the original and trimmed .fastq files (four files in total) using directories as ouputs with the directory() flag.

- The container image can be found at

https://depot.galaxyproject.org/singularity/fastqc%3A0.12.1--hdfd78af_0

Answer

This makes the rule definition quite ‘simple’ compared to solution 4:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 | |

.snakemake_timestamp

When directory() is used, Snakemake creates an empty file called .snakemake_timestamp in the output directory. This is the marker file it uses to know whether it needs to re-run the rule producing the directory.

Overall, this rule works quite well and allows for an easy rule definition. However, in this case, individual files are not explicitly named as outputs and this may cause problems to chain rules later. Also, remember that some software won’t give you any control at all over the outputs, which is why you need a back-up plan, i.e. solution 4: the most powerful solution is still to use shell commands to move and/or rename files to names you want. Also, the Snakemake developers advise to use directory() only as a last resort and to use touch() instead.

This option amounts to let FastQC follows its default behaviour but manually rename the files afterwards to obtain the exact outputs we require.

Exercise: Implement a single rule to run FastQC on both the original and trimmed .fastq files (four files in total) and rename the files created by FastQC to the desired output names using the mv <old_name> <new_name> command.

- The container image can be found at

https://depot.galaxyproject.org/singularity/fastqc%3A0.12.1--hdfd78af_0

Answer

This makes the rule definition (much) more complicated than solution 3:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 | |

This solution is very long and much more complicated than the other one. However, it makes up for its complexity by allowing a total control on what is happening: with this method, we can choose where temporary files are saved as well as output names. It could have been shortened by using -o . to tell FastQC to create files in the current working directory instead of a specific one, but this would have created another problem: if we run multiple jobs in parallel, then Snakemake may try to produce files from different jobs at the same temporary destination. In this case, the different Snakemake instances would be trying to write to the same temporary files at the same time, overwriting each other and corrupting the output files.

Three interesting things are happening in both versions of this rule:

- Similarly to outputs, it is possible to refer to inputs of a rule directly in another rule with the syntax

rules.<rule_name>.input.<input_name> - FastQC doesn’t create output directories by itself (other programs might insist that output directories do not already exist), so you have to manually create it with

mkdirin theshelldirective before running FastQC- Overall, most software will create the required directories for you; FastQC is an exception

- When using output files, Snakemake creates the missing folders by itself. However, when using a

directory() output, Snakemake will not create the directory. Otherwise, this would guarantee the rule to succeed every time, independently of theshelldirective status: as soon as the directory is created, the rule succeeds, even if theshelldirective fails. The current behaviour prevents Snakemake from continuing the workflow when a command may have failed. This also shows that solution 3, albeit simple, can be risky

Controlling execution flow

If you want to make sure that a certain rule is executed before another, you can write the outputs of the first rule as inputs of the second one, even if the rule doesn’t use them. For example, you could force the execution of FastQC before mapping reads with one more line in rule read_mapping:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 | |